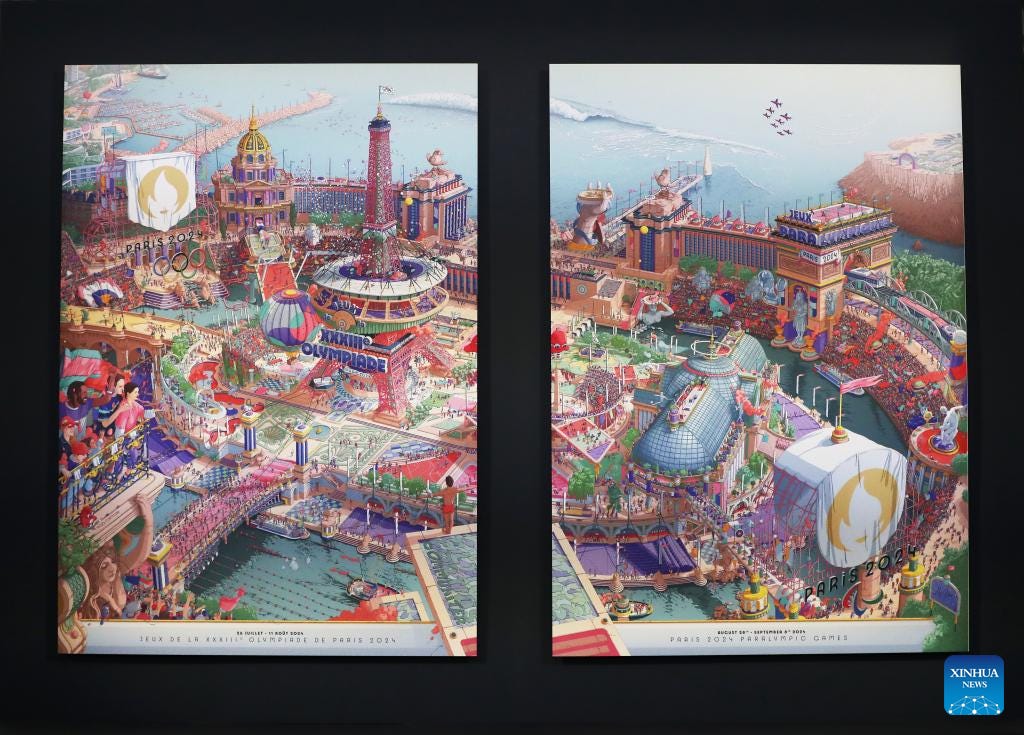

A couple days ago the Associated Press put out a piece on the return of art deco after nearly a century of relative obscurity in the design world.

My first thought was “hell yeah,” because art deco rips.

My second thought is that it would be nice to see some designers with actual industry experience take a crack at what this style looks like in the 21st century. Art deco (and steampunk, etc.) has been painstakingly kept alive through the internet by people who look like this:

And while we should thank the weird dweebs for their service for their quasi-autistic archiving of everything related to these styles, it’ll be interesting to see what design firms with actual resources will create, provided this isn’t another microtrend du jour (to be honest, I think this will stick around for a while — we’ll get to that in a little).

I’m gonna cut to the chase right now and tell you that the main thesis of this article centers around the modernists (as in the cultural movement of the early 1900s) winning out in the design world due to a number of reasons, forcing us in the direction of a minimalist design ethos, resulting in a natural correction towards opulence in design.

Still, modernism ended in the 1970s and we’ve been in a sort of postmodern (maybe a post-postmodernism at this point?) haze of unclear, decentralized design. This has created some genuinely intellectually-stimulating pieces and areas, and has also generated a heap of navel-gazing nonsense.

The world has, nonetheless, moved toward a more austere design vernacular in the contemporary space, initiated by the modernists over a century ago. The design pendulum (and in truth a lot of pendulums) is swinging back in the direction of human-first design at near-breakneck speeds, as we see an increasing number of institutions looking to “give the people what they want“.

Two Roads Diverged In a Chrome-Plated Wood…

As always, let’s start at the beginning:

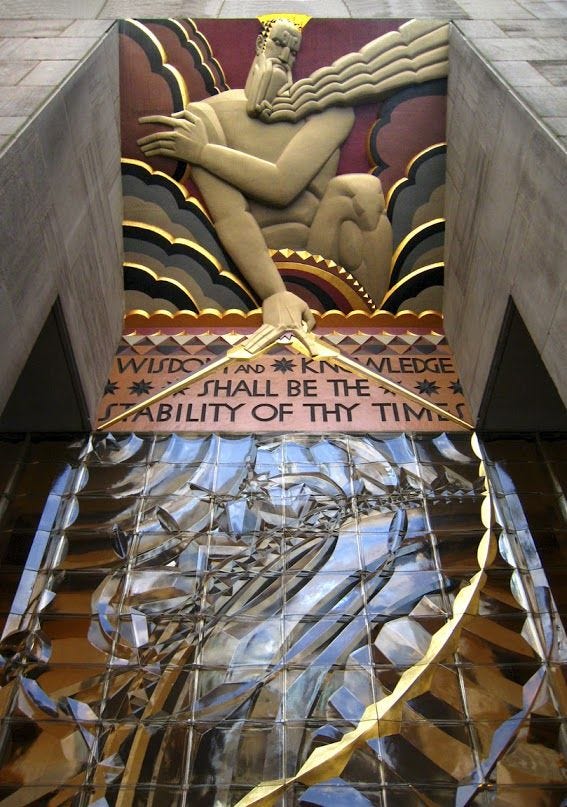

Art Deco originated in France in the mid-1910s as an avant-garde movement. The style itself evoked themes of ascendant glamor, focusing on streamlined geometric forms in vibrant, high-contrast color palettes.

The style itself began its rise to prominence alongside the start of World War I. After the conclusion of the Great War, the French government hosted the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, as a means to show off this new modern style, then stylized as “Zigzag Moderne“.

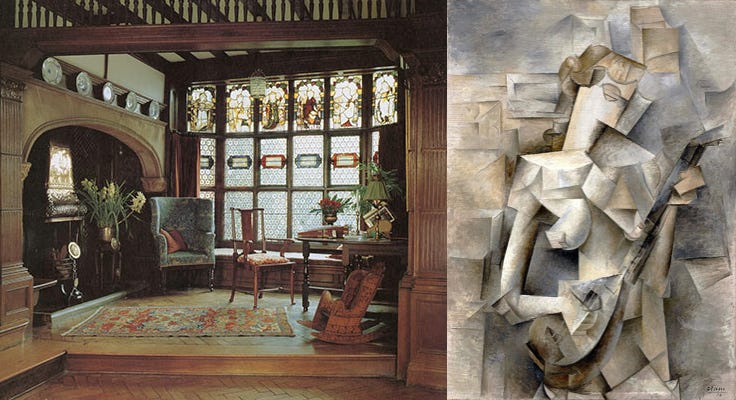

Although part of the broader scope of the modernist movement, art deco differed in a very significant way from some of the other prominent schools of the time (e.g., the Bauhaus), in that it embraced grandiosity and ornamentation, taking cues from the arts and crafts movement, art nouveau, and cubism, and combining them with themes and motifs from ancient civilizations like the Greeks, Egyptians, and Aztecs.

In particular, art deco took the more organic shapes associated with art nouveau and replaced them with powerful, angular shapes and sculptures, playfully mixing them with the streamlined forms that signified a prosperous and modernized, robust industry. Art deco was as aspirational as you could get, and the Western World was largely living up to that characterization through the 1920s.

Of course, this all changed on October 24, 1929, better known as Black Thursday. The US economy took a shit and completely imploded, taking much of the West with it. This was the beginning of the end for our beloved art deco, even though the style remained very popular well into the 30s.

The final nail in the coffin for art deco, as you might expect, was the onset of World War II. As funds were directed away from public works and towards the war effort, measures of austerity were put into place instead. The war obviously had a devastating impact on the economy of Europe (though it bailed the US out of its depression), and the styles of the time soon began to reflect and favor that.

A genpop prototypal representation of modernism is liable to look a lot like the International style - a stripped-back, minimal design philosophy that greatly (and maybe even over-) emphasizes functionality and utilitarian principle.

In truth, modernism at large leveraged some of the technological advancements in construction technologies, such as reinforced concrete, that made traditional means (e.g., bricklaying) of house construction economically obsolete. This gave architects way more control over the structures that they built, allowing them to play and experiment with forms, often distilling them down to their purest elements.

At the same time, modernism as a philosophy was pretty democratic in nature. Proponents of the early movement believed that architecture should leverage the new age construction technologies to produce cheap, well-constructed, buildings available to the everyman.

In other words, the mantra “form follows function“ was not just a fun saying, but a way to judge the aesthetic merit of a project — the closer the fit of a building was in terms of fulfilling its function, the more valuable it was from the perspective of the modernist.

As you can imagine, the modernists really hated the more “traditional” modernism that art deco represented. In their eyes, this was a style only for the wealthy, due to the price of custom ornamentation.

What developed in the years following the war was a style that was supposed to be indifferent to its surroundings, standing as a broadly applicable set of design principles that are equally at home in the heart of NYC as they are in South Sudan. This blatant eschewing/ignorance of cultural vernacular, while considered a landmark success among the high-minded professionals, was (and continues to be) rather unpopular with those forced to live and interact with their decisions… Does this sound familiar?

Still, international style (and modernism writ large) continued to be extremely popular among the likes of Le Corbusier and Mies Van Der Rohe, flourishing across Western Europe and the United States to the point where "You got off an airplane in the 1970s, and you didn't know where you were". Architects eventually grew bored of the formulaic-ness of these modernist styles that they polluted the downtown of every major city with, and sought to re-introduce elements of flourish and ornamentation to their spaces, ushering in the era of postmodernism.

Take the Westin Bonaventure hotel (the above photos): This is a really cool and interesting design!! Not all postmodernism is bad!!

The architect, John Portman, layered interesting design with an artistic statement, by “peripheralizing the central and centralizing the peripheral”. I haven’t been there personally, but I’ve watched a few youtube videos on the hotel, which makes me an expert here.

Do you have to like this statement? No, of course not. Is this statement even really useful from a human perspective? Also no - the building itself is disorienting and the shops within often receive no foot traffic due to its confusing layout. Despite that, the question being posed is unique and worthy of exploration, and Portman managed to do so in a way that is aesthetically interesting.

My main problem with postmodernism is that they’ve re-introduced flourish and ornamentation, and often these massive postmodern public works projects come with ridiculous price tags. A complete and utter inversion of the principles that the modernists first established.

In my mind, we’re kind of back at square one here — we have these massively expensive buildings that are also hostile to the user AND they’re disgustingly expensive. What if we had just kept the ornamental styles in the first place? Why not just retvrn to neoclassicism or something, like the greek statue PFPs alway suggest on twitter?

I don’t really think we could answer that in any meaningful way here, except that there would be some level of design fatigue that probably would have pushed us toward hyper-minimalism and an extreme aversion for visual clutter anyway, before a grandiose shift back (i.e., exactly what we did anyway, on a slightly different timeline). Plus, you can’t really go backwards… Retvrning to neo-neoclassicism or the like is pure simulacra anyway.

But, if we’re gonna spend hundreds of millions/billions of dollars on buildings anyway, we can at least direct those funds toward making the buildings beautiful and enjoyable to the public.

An Ode to New York City

While art deco broadly made its mark across the American landscape with significant installations in Chicago, Los Angeles, Cleveland, Albany, and more, its most prominent impact was on the skyline of New York City.

Our AP article from the beginning of this newsletter closes with a quote from art curator Lilly Tuttle, saying “More than an aesthetic, Art Deco was the look that sold the city to the world”.

That was and remains true to this day — the aspirational style of art deco has seeped into the very core of the city, and hordes of young, ambitious people the world over have set their sights on rising to the top here.

While the influence has certainly faded into the background over the last hundred years, its effect on the city itself is unmistakable.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Frayed Collar to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.